In Part One of this interview with DJ Woody Wood, the Three Times Dope member reminisced on his early introduction to the Philly Hip-Hop scene. In this second instalment, Woody remembers signing with Lawrence Goodman’s Pop Art / Hilltop Hustlers label and recording the group’s debut album “Original Stylin'”.

So was it easy to get your music heard by Pop Art’s owner Lawrence Goodman considering the label was based in Philadelphia?

“Man, Lawrence’s office was all the way up in West Philly on City Line Avenue near the skating rink. I had a car back then and no matter the weather, rain or snow, me and Chuck would drive up there. But Lawrence Goodman would never come out. We never saw this dude (laughs). But there was this lady, Miss Joanne on reception, and we would give her the music and she’d be like, ‘Okay, I’ll let him hear it.’ Then she’d call us back like, ‘Well, Lawrence said go back to the drawing board. He didn’t really seem too impressed.’ So we’d go back to the drawing board.”

So is this around the 1985 / 1986 period?

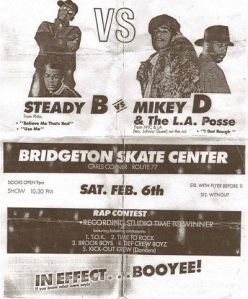

“Yeah, this was in 1986. By that time Lawrence had more cats on his label who’d come out from both New York and Philly who were really starting to make some noise like Craig G and Steady B. We had these big concerts in Philly around that time like the Fresh Frest and Philly Vs. New York. You’d see some of the Philly guys who I was telling you about before battling the emcees and deejays from New York at these events. It was at those events that it really became apparent to me that the deejays from Philly were so much better than the deejays from New York. It was like the New York dudes hadn’t had enough practice when they came here (laughs). They really couldn’t mess with the dudes in Philly when it came to deejay-ing. When it came to the emcees, that was more of an even battle, but as far as the deejays were concerned, it definitely felt like we had more deejay power here in Philly. I mean, I was always impressed by the cats from New York, but I was more impressed by the deejays I could physically see in Philly. That was also around the time when I started hearing about people like Jazzy Jeff and Cash Money who did things differently to everybody else. I’m listening to the tapes and Cash Money was doing stuff like taking the ‘It’s time…’ part from Hashim’s “Al-Naafiysh” and just cutting between the two copies so quickly, like ‘It’s t-t-t-t-t-t-time…’ and then he started transforming and I’m like, ‘What’s that?’ That changed deejay-ing in Philly at that point. Jeff, Cash Money, Grand Wizard Rasheen, those dudes just had something that was so different that really caught the attention of everybody.”

So at what point did you make something that Lawrence actually liked?

“Lawrence kept telling us to try something else and we kept going back with more music. We kept working with different emcees. We did something with a guy called Bay Ray Boogie who sounded like LL and Lawrence was like, ‘Try something else.’ So we went back again and that’s how we met EST”

How did EST become part of the group?

“Well, EST was still in high-school at that time. We met him and he started coming around. Rob (EST) was definitely pretty thorough and had his own little style. He was a creative dude. He’d carry this book around with him and doodle all the time, drawing stuff. So we did something with EST, sent it over to Lawrence and he was like, ‘Wait a minute, let me talk to you guys.’ So we went up to see him and that was how we met Lawrence Goodman. He’d just signed Steady B to Jive at that point and had all these connections and that was when he started the Hilltop Hustlers. He signed Cool C first and we were like, ‘Damn! We’ve been waiting, why’s he not signing us?!’ Eventually he did sign us and that’s when I really started to see how the music scene worked.”

How familiar were you with Steady B and Cool C at that point?

“Well, Steady had already had records out like “Bring The Beat Back” so I was very familiar with him because it was actually through looking at the back of his records that we found Lawrence Goodman. I didn’t know Cool C at the time. I mean, he was there but I didn’t know him until we got with Lawrence. Cool C didn’t have records out before like Steady B had. I think what Lawrence saw was that they had MC Shan out in New York at the time and Cool C sounded a little like Shan. I think Lawrence was smart enough back then to understand how the music game worked and he used that to mimick what some popular artists were doing and diss them which was a big thing in Hip-Hop at the time. I mean, if you dissed somebody back then it was huge.”

Steady B dissed LL Cool J with “Take Your Radio” and then Cool C went at Shan with “Juice Crew Dis” – what was the reaction on the streets of Philly when two local artists went at two of the biggest Hip-Hop artists out of New York at the time?

“I mean, I think all of that was really down to Lawrence. I think he had relationships with those guys in New York and I don’t know what happened with those relationships or if he was just capitalising off the battle scene that was in New York at the time with the whole BDP / Juice Crew thing. I think he was smart enough to think of doing some of the same thing in order to get some attention. But at the same time, although some people in Philly might have been surprised to see local artists dissing big New York artists, there was also a sense of ‘Yeah, give us our space to.’ I mean, MC Breeze had already made the song “It Ain’t New York”. It wasn’t like we were some know-nothing dudes down in Philly. We wanted our respect to. But I mean, back then, if you dissed somebody, it wasn’t like now where it’s like you’re trying to kill them, it was about going for your reputation. It was healthy competition.”

So getting back to EST, what were your first impressions of him as an emcee?

“What ES brought to the table with his lyrics and the kind of stuff he was writing was just very creative to me. I mean, we all had a mutual respect for what each member brought to the group. I’m about four years older than EST and Chuck is a year or so older than me, so we definitely had more experience than ES in terms of what we’d been doing with the deejay-ing, but we just came together so well as a group. ES definitely had his own style. He was left-handed. He always wore K-Swiss. He had his own style with his clothes and his dancing. But remember, EST was still in high-school when we got together. I mean, when our first album came out he was in twelfth-grade (laughs). But to me, EST didn’t sound like anybody else who was out at that time and that was definitely one of things I really liked about him as an emcee.”

It’s crazy to think EST was so young on those early records because he had this big voice and always sounded so self-assured and confident…

“I agree. You saw that to when we were doing shows. I mean, when we started doing shows it was new for all of us, so we were all learning as we went along. But EST definitely had that presence. I remember when we started out, Lawrence used to package Steady B, Cool C and us all together for shows, so if you wanted to book one of us, you got all three of us, and that’s how we got a lot of our early exposure. Steady was already out first, but although Cool C got signed before we did we kinda came out around the same time with records. So we would sit down in Lawrence’s basement and do all three shows together. We would go first, then Cool second and Steady B last. So when you came to one of our shows, you’d see 3-D doing our stuff, then we would stay on the turntables and the beat machine and Cool C would come out and do his show, then Steady would come out with no intermission. We would just go straight through and it was bangin’. The only thing we would switch was a Hilltop Hustlers sign we had when we were onstage because Steady had his own sign and everybody also had different dancers. But performing all together like that was definitely beneficial for everyone.”

Where did the Hilltop Hustlers name come from?

“Well, Lawrence had his label Pop Art and then at some point he decided he was going to change it to Hilltop Hustlers Records. Steady B was from the Hilltop, which was 60th and Lansdowne in West Philly. So with Steady, Cool C and us they probably just decided it would be good to put us all under one name, the Hilltop Hustlers. The original Hilltop Hustlers were a gang back in the 70s in Philly, so he just took that name and used it.”

Was there ever any feedback from any of the gang’s members about the name being used by you all?

“I don’t think so, but then I wasn’t from Hilltop so I probably wouldn’t have heard it as much as someone like Steady would have done. But they probably didn’t think it was a bad thing because it was positive to take a name that had been used before and use it again in a way that was showing respect for where it came from. But you see, 3-D, we came from Hunting Park in North Philly, which is why you would hear EST say on records, ‘From Hunting Park, the Hilltop…’ so that we were giving respect to where we were from. We wanted to let people know the neighbourhood we were from, but we were also respectful to the Hilltop because we were under that name Hilltop Hustlers and we were all working together at that time.”

Radio always seemed like it played a big part in the Philly scene back then…

“It was crazy. We had two big stations here in Philly, WDAS and Power 99. Now you had Lady B on Power with “The Street Beat” and Mimi was on WDAS with “The Rap Digest”. All these cats from New York used to come Philly to get on the radio and I was trying to understand why they would do that. I used to ride with Lawrence back and forth to New York to drop off our music and that was when I realised that those dudes in New York were battling so hard. You had Kiss and WBLS with DJ Red Alert on one and Mr. Magic on the other station and they had beef with the whole KRS-One / MC Shan battle. So if you were affiliated with one you couldn’t get on the other station. So you had some of those dudes coming down to Philly, which was a major market with two large stations, and getting a lot of air-time. We’d see this as we bounced from station to station and that’s when it became apparent to me that we were really onto something as a group because we sounded just as good as them. In fact, when we first started getting heard outside of Philly around 87 / 88 people actually thought we were from New York because of our sound.”

That time around 87 / 88 seemed to be a real break-out period for Philly artists…

“That whole era was crazy. I mean, if they’d have had reality TV back then (laughs). There was so much stuff going on up at the radio stations and it was just so much fun. On any given Friday night, either on Mimi’s Rap Digest or Lady B’s Street Beat, you’d have Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, 3-D, Cool C, Steady B, Malika Love, DJ Bones, Tuff Crew, everyone would be up there.”

Now just to clarify, you weren’t the same Woody Wood who was a mix deejay for Lady B in the mid-80s?

“Nah, there was another guy who used the name Woody Wood from Jersey so that wasn’t me.”

Were there ever any memorable battles at either of the stations considering the amount of artists who used to congregate at each spot?

“Yeah, yeah (laughs). Steady B and the Fresh Prince went at it one time on-air. This was about 87 / 88. I mean, for the most part everyone had mutual respect for everyone else, but of course everyone wanted to be seen as the best. Steady had more street credibility at that time, but that was maybe one of the first times that people outside of those who really knew him saw a different side to the Fresh Prince, like, ‘I may sound a certain way but don’t play me, I’m from Philly to!'”

At the time you would have been recording 1988’s “Original Stylin'” project there were a lot of classic albums coming out from Public Enemy, Big Daddy Kane, Eric B. & Rakim, Biz Markie etc – what was your mindet going into making that debut album considering what else was happening in Hip-Hop back then?

“At the time, for me, I was just thinking that we wanted to sound different. Hip-Hop was just so creative back then and we really wanted to just sound like us. I felt like what we came up with on that album was a good mix of stuff that did make us stand out. We didn’t sound like anybody else and each one of us in the group brought something to the table. We all had an input on that album. But that was the case from the very beginning. I mean, our first songs, “On The Dope Side” and “Crushin’ & Bussin'”, I felt took sounds from that era, like “Funky Drummer”, but we were trying to do different things with them. We also had some creative input from Steady B early on as well as he produced “From Da Giddy Up”. The track was originally for Cool C but it was a little too fast for him. But that beat was something that Steady had come up with and DJ Tat Money actually cut on that record. So yeah, it was too fast for Cool C to flow to, so EST sat down and wrote something that became “From Da Giddy Up”.”

I remember at the time being impressed with how much of a really solid, clean sound that first album had to it, particularly on tracks like “Believe Dat” and “Straight Up”…

“Yeah, that sound came from Chuck and Lawrence and the studio we were using at the time. We were working in Studio 4 in Philadelphia at the time with Joe ‘The Butcher’ Nicolo as our engineer. I definitely give those guys credit for what they did when it came to the overall sound of the album. I can’t take credit for any of that (laughs).”

I think the vinyl album came out here in the UK on the City Beat label a little earlier than it did in the States on Arista…

“Yeah, we were signed through City Beat in the UK. I mean, Lawrence was the business person behind what happened on that side so I’m not really sure why that was that we were signed to two different labels like that. To be honest, that was part of our challenge with some of the other stuff that happened on the business side. But we were signed to two different labels, had two different versions of our first album, and some of the tracks that were on the US version weren’t on the version that came out in the UK through City Beat.”

Yeah, “Funky Dividends” wasn’t on the UK pressing and “Once More You Hear The Dope Stuff” came as a bonus 12″ with initial copies of the vinyl version…

“I mean, we weren’t privy to a lot of the business stuff back so we didn’t really know what was going on.”

What was the impact of the album both in and outside of Philly?

“Good question. I mean, the album actually came out a little earlier in Philly. In fact, from what you said, I would say it came out in Philly the same time it came out in the UK. So people in Philly had the single “Greatest Man Alive” before everyone else had the single. That was also the first video we ever did which really opened up a lot of doors for us. Even though we were going through some internal things with the label that video still got made. When I first saw that video I was shocked because they’d done a really good job for the amount of money that was actually spent on it. But when it dropped we started realising that people outside of the Philly area, New York area, Virginia and D.C. were also picking up on the music. We could see it, because right away we started getting more fan mail (laughs). We used to have a PO Box in Hunting Park and we would open these letters and there’d be girls sending pictures and stuff like that (laughs). It was crazy to me. We used to sit there and laugh and be like, ‘Damn, people really like us.’ I wouldn’t say I was totally shocked at the time but to see people from other areas liking our music was definitely a positive thing. I still have some of the fan letters today (laughs). I’m telling you, I keep all that stuff. I’ve still got receipts for equipment, I’ve got pictures from back then, I didn’t throw anything away (laughs).”

You mentioned that there were some internal problems between the group and the label when you were making the “Greatest Man Alive” video – so things were coming to a head with Lawrence Goodman that early on?

“Oh yeah. I mean, we were cool, but it was hard at that time because we were starting to have different views on things. I mean, Lawrence was doing a good job, but he was both our manager and our record label at the same time. So we started to see there was a conflict there. I think he meant well, but we felt that some of the things that were happening weren’t in our best interests. We found out about some things and had somebody look at our contracts. Now, as I said earlier, EST wasn’t eighteen-years-old when we were first signed and his mother never really signed his contracts and stuff. So he got pulled out the group someway and then we got signed directly to Arista. There was just a whole bunch of stuff going on.”

Ryan Proctor

Read Part Three of this interview here.